Huntington’s disease is a hereditary, neurodegenerative brain disorder for which there is currently no cure. HD onset typically occurs between the ages of 30 and 50 and symptoms vary from person to person, though progression of the disease causes cognitive, motor, and behavioral decline. The average lifespan after HD onset is 10-20 years and children with an HD-positive parent have a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. For more information regarding HD, please visit hopes.stanford.edu

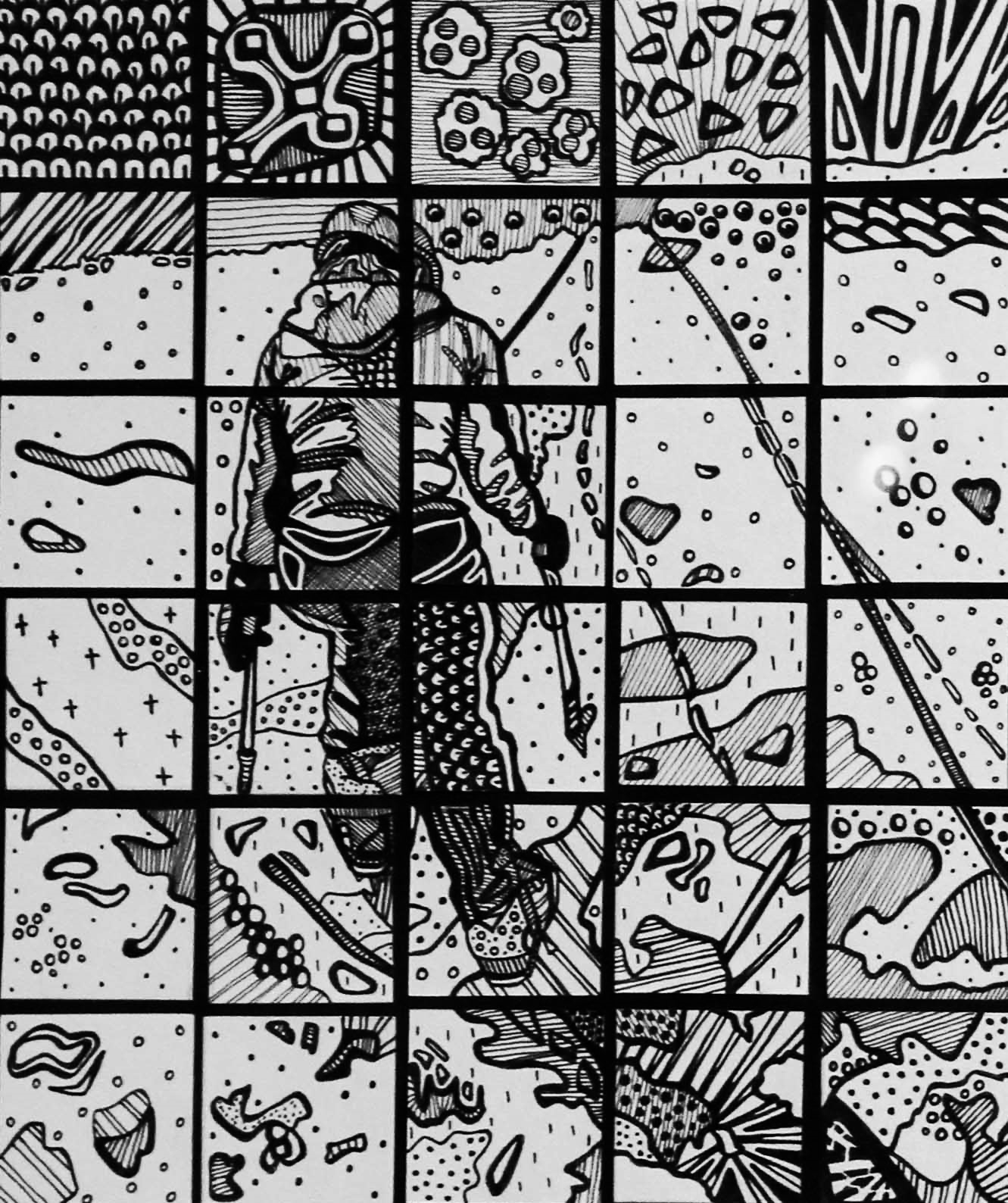

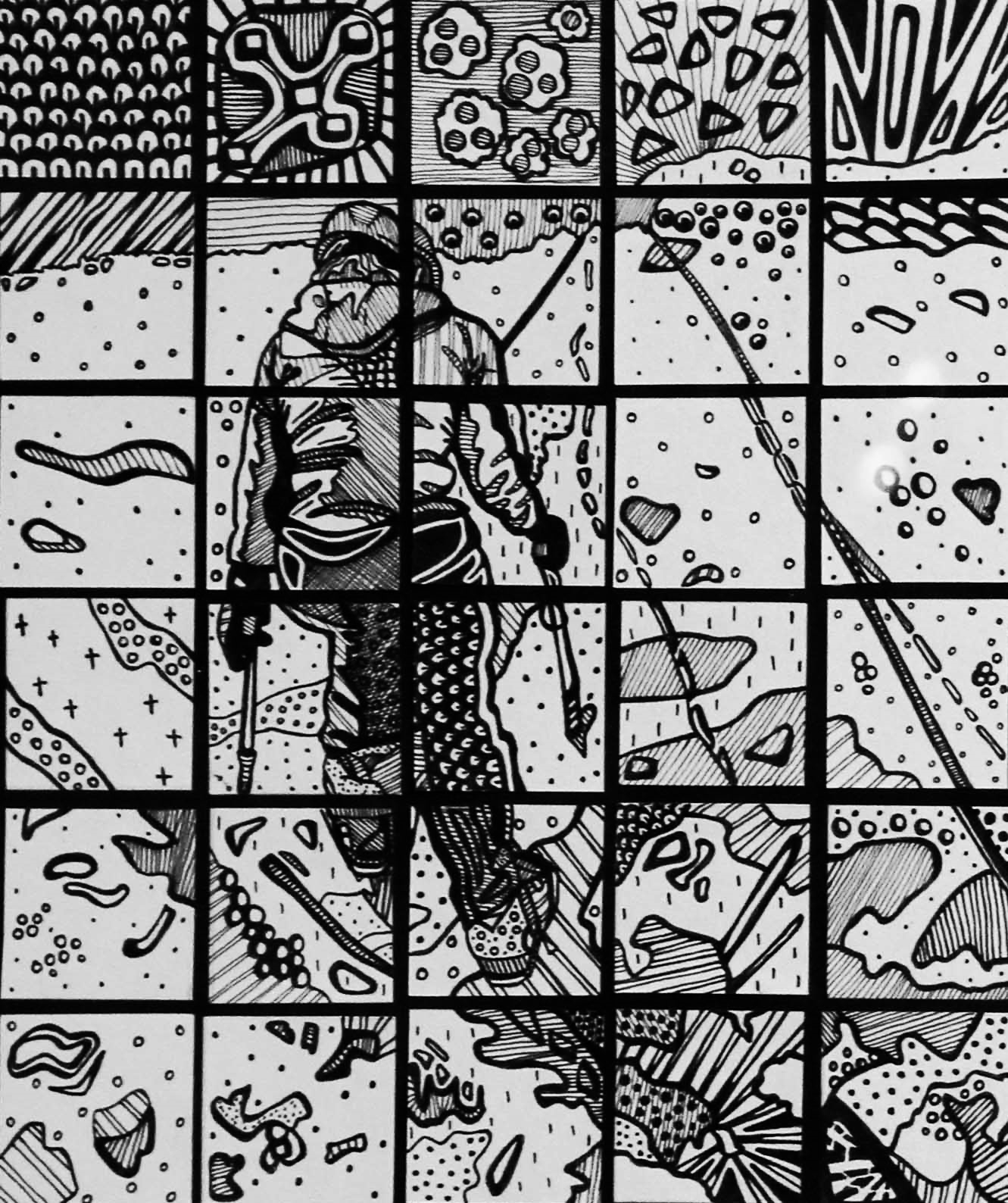

The title Fragmentation was inspired by the disease progression of HD and the recognition that over time, what was once known by a patient, caregiver, or friend is broken down, reordered, and degraded. The decision to depict portraits fragmented along a square grid was guided by the notion that while individuals faced with incurable disease and disability are often unfairly placed in both categorical and clinical boxes, their stories often transcend textbook diagnoses and physically-based assumptions. This show works to spread HD awareness and give space for affected individuals to share their stories, beyond the clinical setting. Each individual’s story is much more involved than Annie was able to display through imagery or words, but the partial goal of this project was to give individuals the opportunity to vocalize personal stories, with hopes of having the act of telling one’s illness narrative be a reflective and healing process. Through the completion of drawings loosely based on these narratives, Annie was also able to reflect on and better understand the inspirational stories of those affected by HD.

This show is a culmination of Annie’s work with both the Huntington’s Outreach Program for Education, at Stanford (HOPES) and members of the Palo Alto HD Support Group. In order to protect the privacy of individuals interviewed, all names have been changed.

After obtaining degrees in physics, law, and economics; serving as a lawyer/economist in the Office of the President for both President Ford and President Carter; and founding a company that produces computer-assisted thinking software, Michael acknowledges that he has lived a life most only dream of. But HD runs in his family. His father died of it, his son tested positive, and his 27-year-old daughter is at risk. Being diagnosed with HD as well as surviving cancer has led Michael to pursue things that bring him happiness in retirement. He currently sings in the Berkeley Community Chorus, rides his bike, and practices Qi Gong.

At support group meetings, Michael is eager to speak to the group and isn’t shy when it comes to discussing HD. When asked what motivates his openness regarding his experiences with HD, he responded:

“One is that I’ve survived leukemia. Every day I live is like a gift. Two, is I want to have a good life right now. I tell people of course I have Huntington’s disease and it helps them understand where we’re coming from. And I think it’s a more interesting way to live to talk.”

Dating since the age of 15, Jim and Mary have been married for 41 years. Despite early knowledge of HD in Jim’s family and his diagnosis in 2000, Mary’s commitment to her husband has been unwavering.

“We’re both Christians. We both rely on faith and we both believe that God’s in control…that’s what keeps us going.”

“Not to say that it’s easy...It’s not easy. There are times we just want to pull our hair out.”

“I already beat you to that,” Jim points out to his wife, referring to his balding head.

The ensuing laughter offered a brief respite from his reality with HD - an inability to continue practicing as a mechanical engineer, reliance on two trekking poles to walk, and the knowledge of what’s to come after caring for both a father and grandmother with the disease.

Lisa is the caregiver of Sean, her spousal equivalent of 29 years. What surprised me more than her story was the ease with which she spoke. Throughout the interview, Sean reclined in the adjacent room, unable to speak or walk, though clearly paying more attention to my presence than his routine Wheel of Fortune viewing. Before leaving, Lisa was sure to show me a scrapbook Sean’s mother had made for his 40th birthday. Inside were countless images of Sean playing baseball or showing off his charismatic smile and muscular build. When asked how she stays so incredibly positive despite the waning of Sean’s mental and physical abilities over the years, Lisa mentions The Precious Present, a book her sister gave to her around the time Sean was diagnosed with HD.

“It’s about not dwelling on the past, not worrying about the future, just thinking about today, because today’s the gift.”

Laura’s husband has symptomatic HD. They have two daughters, ages 19 and 21. Neither has been tested.

Laura has come to terms with the fact that her husband and life partner will likely die within the next decade. What forever occupies her mind, however, is that both daughters are at risk. She and her husband had children knowing he was HD positive.

“They were saying ‘Oh in 20 years from now there will be a cure.’ Now I know that’s bullshit. When somebody asks you should I have a baby or not, the answer now is no. It’s not like everything is valid and everything is a choice you can make…when you take the risk that child takes the consequences.”

Maureen shows that even before the onset of obvious symptoms, being positive for HD can be pervasive in one’s everyday life. After recently losing her driver’s license due to the DMV’s knowledge of her neurodegenerative disease, she has become increasingly frustrated.

“One of the things that I tend to do is I can’t get these things out of my brain. I worry all the time, I’m stressed all the time because I can’t get things out of my brain...Even if I pass the drivers test, I may have to get new insurance and how much is that going to cost?”

Seeing the conversation quickly becoming dominated by the negativity surrounding the DMV, Maureen’s husband Brian interjected:

“But anyway. We went to the bicycle shop this afternoon.”

David and his wife Maureen are both musicians. Maureen was trying to find an accompanist for a piece she was playing on violin and put an ad up in the music department at Stanford. Though he worked as a programmer, David decided to take a piano class at Stanford.

“I went to the music department just to browse around and came across an ad. All the numbers had been torn off except for one.”

Maureen hasn’t picked up her violin for some years, but David has encouraged her to start playing piano again as a subtle attempt to delay the onset of HD symptoms.

Despite watching both her grandmother and father develop symptomatic Huntington’s disease, Sarah shows that testing positive is not always negative. After graduating from Stanford law school and securing a position in an east coast law firm, testing positive for HD helped her to reevaluate what she finds most meaningful in life.

“I practiced in Washington D.C. for two and a half years when I quit my job and went up to Alaska to become a mountain guide.”